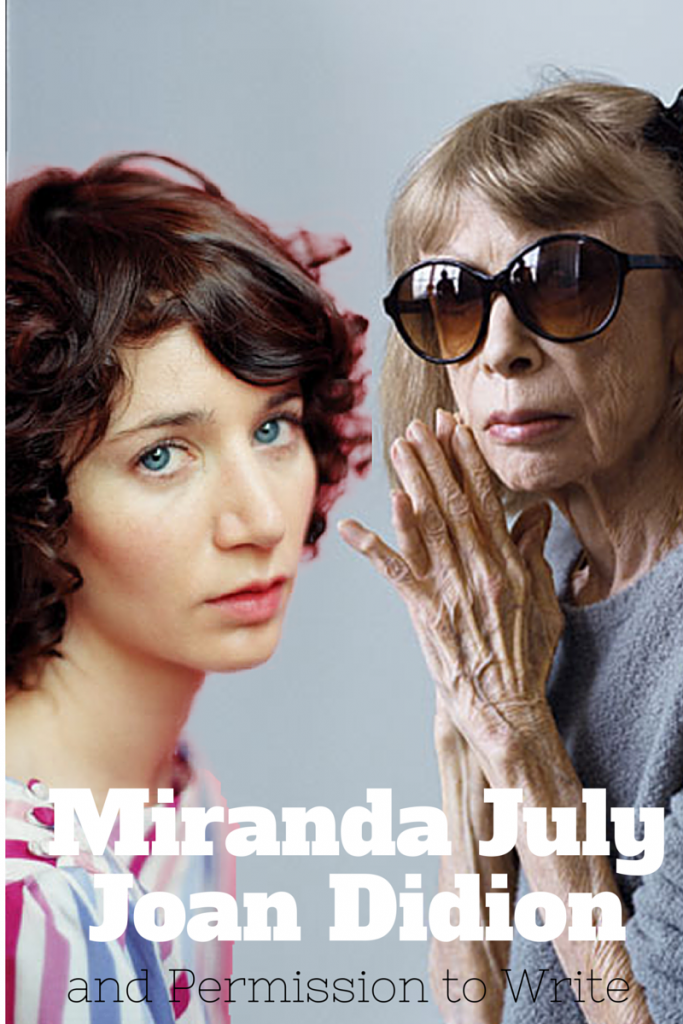

Reading. Let’s face it, that’s what got most of us into this writing business. And it’s what keeps most of us going, at the end of the day. Am I right? At present, I am reading Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking and Miranda July’s collection of short stories, No One Belongs Here More Than You, simultaneously. Or rather alternately, but interwoven—the first in hardcover and the second on my phone.

Each of these remarkable creators is a masterful writer, entirely different in voice and yet so confident and rich and upfront. There is another similarity I’d like to try to articulate: they both use theme as an organizing principle in a way that is incredibly effective and moving, without rendering the stories flat or abstract, without detracting from build, from a desire to know what is going to happen, even if it’s not always what is going to happen next chronologically. Sometimes it’s more a question of what will happen next thematically.

Didion keeps coming back to the magical thinking—the refusal to accept on some profound level that her husband, who has died on the first page or actually months before the first page, is dead. For example, chapter four begins, “On most surface levels I seemed rational. To the average observer I would have appeared to fully understand that death was irreversible.” (42)

As she circles through what happened the day her husband dies, and before—just before and years before—and after—minutes after and months after, it is the progression of the theme that keeps us gripped in the narrative.

In a funny way, Miranda July organizes her stories by theme as well. They have these wonderful voice-driven internal logic that takes us from scene to scene and thought to thought, circling through time but hitting the theme again and again. It builds to story, and is marvelously entertaining.

For example, in “It was Romance,” a story about a class on romance, about isolation and connection and then the awkwardness of separating again, of the ultimate state of separation no matter what intimacy has been achieved, the final image resounds with this theme:

“There was no system for stacking [the chairs], so we accidentally made many substacks that were too heavy to lift and join together. The stacks of various heights stood alone. We gathered our purses and walked to our cars.”

I guess without knowing it, I’ve been looking for models for just this: organizing narrative by theme without sacrificing story, details, all those pleasures. And in this conversation I’m staging between Didion and July, I found it.

The most important thing I have to say about these books, about any books, is this: reading gives us permission. The sheer courage and clarity, the lyricism or stolidity of other people’s sentences, the bulk and build of their images, the precision of their characters, their risks, give us our own courage, clarity, lyricism. Permission. Gives us access to parts of ourselves we may characteristically think should not exit and therefore neglect to use to create the firestorms and flying wood-chips of stories on the page.

What gives you the guts to grab language and force it to the page? What gives you the impulse to seduce story? What has surprised or delighted, taught you something or reminded you of what was possible in your reading lately? Post your thoughts below, and let’s talk!

Images that I know are there, even if no one else does. It’s a visceral response: I have to tell what I saw.

Great, Melanie. Thank you.